Why Has Aurangzeb Suddenly Become Important in India?

What began as a Ram Navami procession in Mumbai’s western suburbs soon spiraled into a troubling spectacle of hate speech and offensive slogans, once again raising alarms about the deepening communalization of public festivals.

According to various accounts, the procession drew thousands—mostly young men in their 20s and 30s, alongside some older participants and women.

But the tone changed drastically when loudspeakers began blasting hate-filled songs and slogans—not just aimed at communities, but also invoking historical grievances centered around Aurangzeb.

Chants referencing Aurangzeb, the 17th-century Mughal emperor, were used to stoke communal passions—framing him as a historical villain in present-day political narratives.

This trend of resurrecting Aurangzeb’s legacy in modern-day provocations has become increasingly common, especially in political discourse and right-wing mobilizations.

In recent years, the figure of Aurangzeb, the sixth Mughal emperor, has re-entered the center stage of Indian public and political discourse. Once considered just one of many historical rulers, Aurangzeb’s name now evokes strong opinions, passionate debates, and ideological clashes.

From textbook revisions to street renaming controversies, from political speeches to viral social media reels, the Mughal emperor who ruled from 1658 to 1707 has become a focal point of national conversation.

But why? Why has Aurangzeb suddenly become so important in India?

Let us explore this resurgence through historical, political, and cultural lenses.

The latest wave of the Aurangzeb controversy began with the upcoming Bollywood film Chhaava, which depicts the life of Chhatrapati Sambhaji Maharaj and prominently features Aurangzeb as his adversary.

The portrayal stirred strong reactions, especially from right-wing groups. The Bajrang Dal escalated tensions by openly calling for action against Aurangzeb’s grave in Aurangabad, suggesting it should be removed or symbolically “reclaimed.”

This rhetoric quickly spilled over into the streets. Communal tensions flared, particularly in Maharashtra, where provocative slogans, hate speeches, and inflammatory processions—often invoking Aurangzeb’s name—triggered violent clashes between communities.

On 17 March 2025, communal violence erupted in Nagpur, Maharashtra, India, following demands by right-wing Hindu organizations to remove the tomb of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb.

What began as historical debate has now become a volatile fault line, with centuries-old legacies being used to justify present-day unrest—all in the name of a ruler who died over 300 years ago.

The Historical Figure: Aurangzeb’s Legacy

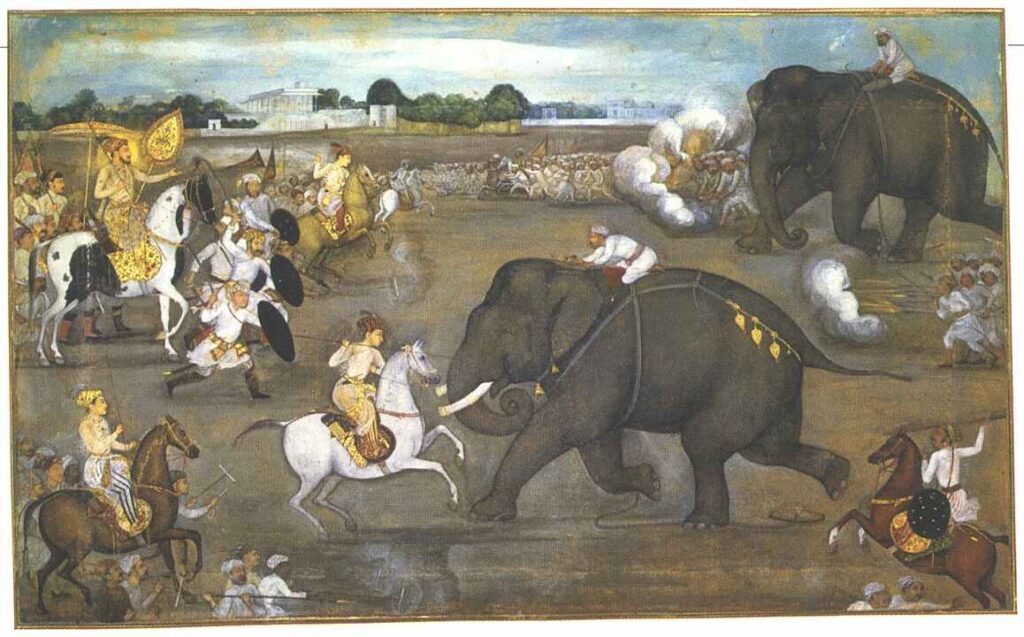

Aurangzeb Alamgir was not just another ruler in India’s long history; he was arguably one of the most powerful emperors the subcontinent has ever seen.

His reign marked the greatest territorial expansion of the Mughal Empire. However, he is remembered not merely for his military conquests but for his ideological rigidity.

Aurangzeb was known for:

- Imposing Islamic Sharia law across his empire

- Re-imposing the jizya tax on non-Muslims

- Demolishing several Hindu temples

- Imprisoning his father, Shah Jahan, to seize the throne

- Executing his own brother, Dara Shikoh, who was seen as a more liberal and syncretic figure

These actions contributed to his image as a ruler who was intolerant of religious pluralism. Over time, his rule has become symbolic of religious orthodoxy and authoritarianism.

Historical Revisionism and Identity Politics

In the post-independence era, Indian history was often narrated with an emphasis on unity and pluralism. Figures like Akbar were elevated as examples of secular leadership, while more divisive figures like Aurangzeb were downplayed. However, in recent years, there has been a shift.

As identity politics becomes more central to electoral strategies, political groups have started re-examining India’s past from the lens of civilizational pride. This includes:

- Highlighting historical wrongs committed against Hindus

- Elevating ancient and medieval Hindu rulers who resisted invasions

- Reassessing Mughal emperors, particularly Aurangzeb, as tyrants rather than rulers

This reframing is seen as a form of “correcting” history, often termed as historical revisionism. In this new narrative, Aurangzeb is not a powerful emperor, but a symbol of centuries-long oppression.

Political Symbolism and Contemporary Relevance

The resurgence of Aurangzeb’s relevance is not academic—it’s intensely political.

In many BJP-ruled states, history textbooks have been revised to minimize the legacy of Mughal rulers. Political leaders invoke Aurangzeb in public speeches as a contrast to modern Hindu nationalist heroes.

The logic is simple: by vilifying Aurangzeb, it becomes easier to draw sharp distinctions between Hindu pride and Islamic rule.

This has led to:

- Renaming of roads and towns that previously bore names associated with Mughal rulers

- Political campaigns positioning historical Muslim rulers as outsiders or invaders

- Cultural debates over monuments like the Taj Mahal, which was built by Aurangzeb’s father

These narratives often resonate strongly with young, nationalist audiences who engage with such content on social media platforms.

The Role of Social Media and YouTube Historians

Social media has played a huge role in reviving the debate around Aurangzeb. YouTube channels, Instagram reels, and Twitter threads frequently feature quick-hit videos or infographics that oversimplify complex history.

These often present Aurangzeb in black-and-white terms: either as a devout villain or a misunderstood genius.

With the rise of nationalist influencers and cultural commentators, history has been repackaged into viral, shareable content. This has:

- Simplified academic debates into easy-to-digest binaries

- Created echo chambers where Aurangzeb is either demonized or defended

- Amplified selective incidents, such as temple demolitions or executions

As a result, the average citizen now has a more emotional than intellectual relationship with Aurangzeb.

Aurangzeb vs Akbar: The Contrast Narrative

Another reason Aurangzeb garners attention is because of the constant comparison with Akbar. While Akbar is portrayed as a symbol of tolerance and inclusivity, Aurangzeb represents the opposite.

This contrast serves multiple purposes:

- It frames a moral lesson: pluralism vs. orthodoxy

- It strengthens cultural pride in syncretic traditions

- It justifies contemporary political ideologies by using historical parallels

Akbar’s Din-i-Ilahi and his engagement with Hindu scholars are juxtaposed with Aurangzeb’s bans on music, temple destructions, and religious conservatism.

The Educational Shift: Textbooks and Curriculum Changes

Several Indian states have begun modifying school syllabi to reflect a more nationalist perspective. These changes often include:

- Reducing the number of chapters on Mughal rulers

- Highlighting Hindu kings like Maharana Pratap and Shivaji

- Introducing more content on ancient Indian sciences and culture

Aurangzeb, as a controversial figure, is often the first to be removed or vilified. These textbook changes reflect broader political intentions to reshape how young Indians perceive their past.

Is This Reassessment Fair?

Critics argue that reducing Aurangzeb to a one-dimensional villain ignores the complexities of his reign. He was a deeply religious man, yes, but also a skilled administrator and a capable military strategist. He successfully held together a massive empire for nearly 50 years, no small feat in any era.

Moreover, temple destruction and religious intolerance were not unique to Aurangzeb; such actions were not uncommon among kings of all religions throughout history.

It is important to realize that several Hindu rulers in history also destroyed places of worship belonging to other religions, including Buddhist, Jain, and sometimes even rival Hindu sects.

This wasn’t always driven by religious hatred—it often had political, military, or sectarian motivations. For example, Pushyamitra Shunga (2nd century BCE) is often cited in ancient Buddhist texts like the Divyavadana, Pushyamitra, a Brahmin king who overthrew the Mauryan dynasty, is accused of persecuting Buddhists and destroying Buddhist monasteries.

A Hindu king of Bengal, Sasanka is known to have cut down the Bodhi tree at Bodh Gaya and persecuted Buddhists, including the killing of Buddhist monks.

Many people in India may not even recognize his name, but it’s important to understand that actions like these were not uncommon among rulers of all faiths throughout history. That makes Aurangzeb no different than other rulers.

The Chola dynasty, for example, favored Shaivism and marginalized Jain and Vaishnava temples during certain reigns.

According to Kalhana’s Rajatarangini, Harsha plundered temples, including Hindu temples, not out of religious zeal but to fund his wars and lifestyle.

History cannot be judged solely through the lens of modern morality. The values, beliefs, and societal norms that guide us today were often very different in the past.

What may seem unethical or shocking by today’s standards was, in many cases, considered acceptable or even necessary in the historical context. To truly understand historical figures and events, we must examine them within the framework of their own time, not ours.

However, this understanding does not mean we condone or justify any acts of violence or injustice, regardless of the era.

Ironically, while modern narratives often paint historical figures like Aurangzeb and Shivaji along strictly communal lines, the real history was far more complex and inclusive.

Aurangzeb’s military and administrative ranks included several prominent Hindu generals and nobles, such as Raja Jai Singh, Raja Jaswant Singh, and Raja Todar Mal’s descendants, who played crucial roles in expanding and maintaining the Mughal Empire.

On the other side, Shivaji Maharaj, often portrayed as the Hindu counterforce to the Mughals, appointed Siddi Ibrahim and Haider Ali Kohari, both Muslims, to key military positions—reflecting a leadership driven more by loyalty and competence than religious identity.

These facts challenge the simplistic Hindu-versus-Muslim framing and highlight that power, politics, and pragmatism often outweighed religious divides in shaping medieval Indian history.

What sets Aurangzeb apart is the scale and documentation of his acts, coupled with his rigid ideological stance.

So, while criticism is not unfounded, complete vilification may overlook the multi-faceted nature of his rule.

And why forget Akbar, the Mughal emperor who is still remembered for his policies of religious tolerance, and cultural integration, and attempts to create a syncretic empire through initiatives like Din-i-Ilahi? Akbar didn’t just rule India—he consciously tried to become part of India, forging alliances with Rajput rulers, marrying into Hindu families, and building a court that reflected the subcontinent’s diversity.

It’s also important to address a recurring myth: the idea that the Mughals were foreign invaders. While their ancestry is traced back to Central Asia, most Mughal rulers, including Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan, were born in India, spoke Indian languages, and considered this land their home.

Their architecture, administration, and cultural contributions are deeply embedded in the Indian landscape—proving they were not just rulers of India, but rulers in and from India.

The Emotional Currency of History

Ultimately, Aurangzeb’s resurgence in public memory reflects how history is used as a tool for modern identity formation. In a country as diverse and complex as India, history is never just about the past—it’s about the present.

When political, religious, and social identities feel threatened or are being reasserted, historical figures become stand-ins for contemporary issues. Aurangzeb, in this context, is no longer just a Mughal emperor—he is a symbol, a metaphor, and a cultural signpost.

Aurangzeb’s sudden importance in India is not due to newly discovered historical facts, but because of shifting political narratives, identity movements, and the changing ways in which history is consumed and understood. His legacy is being used as a mirror to reflect current cultural anxieties and aspirations.

In a time when facts often take a backseat to emotions, and when historical figures are judged through the lens of present-day ideologies, Aurangzeb has become more than just a ruler—he has become a battleground for India’s soul.

Understanding this resurgence requires more than just knowing what Aurangzeb did; it demands that we ask why we are talking about him now, and what it says about us as a society.