Let’s settle this once and for all: the idea that Hindus have always been vegetarian is about as historically accurate as a WhatsApp forward claiming ancient India had Wi-Fi and plastic surgery.

The truth is far juicier—literally. Our ancestors, it turns out, were rather fond of meat, including beef. A 2021 Pew Research Center survey found that 39% of Indian adults identify as vegetarians and the country has the highest number of vegetarians in the world

So how did we go from Vedic feasts featuring sacrificial steaks to today’s politics over paneer?

Buckle up for a deliciously irreverent, yet well-referenced, ride through history.

Vedic Age: When Brahmins Had Beef (and Ate It Too!)

Imagine it: 1500 BCE. A fire ritual (yajña) is underway. Priests chant verses from the Rigveda, and nearby, meat is being roasted as an offering to the gods—and, yes, later eaten. The Rigveda (10.91.14) describes the sacrificial offering of bulls and goats to Agni, the fire god. The Shatapatha Brahmana (3.1.2.21) even explicitly states:

“The horse sacrifice is the best of all sacrifices; the meat of the horse is pure and fit for the gods and for men.”

The Taittiriya Brahmana (3.10.10.1) gives instructions for preparing meat during sacrificial rituals and doesn’t shy away from including cow meat. It states that a cow or bull is sometimes offered during certain rituals honoring specific deities, like Madhuparka (a welcome ceremony for guests or dignitaries).

This wasn’t just ritualistic—Vedic society considered meat-eating acceptable, even auspicious, especially for the priestly class. To quote D. N. Jha, historian, and author of The Myth of the Holy Cow:

“The cow was not inviolable in early Vedic society. Beef was served to honored guests, and to students returning home after their studies.”

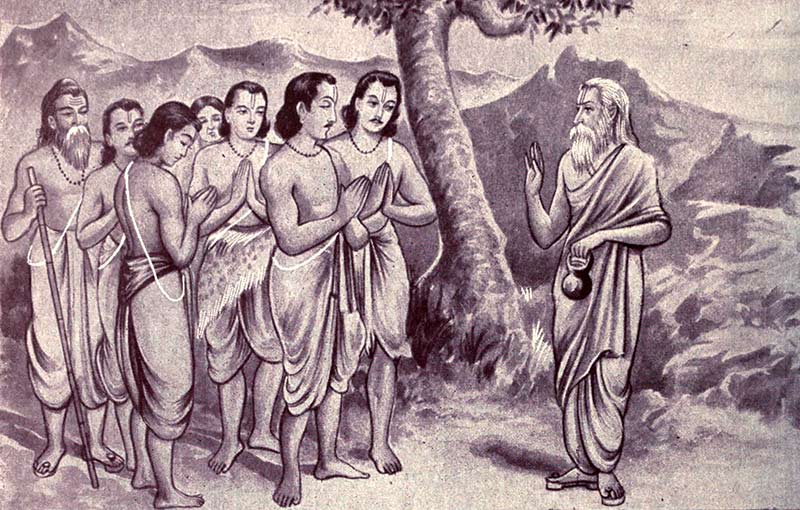

Epic Confusion: Mahabharata and Ramayana’s Mixed Messages

By the time of the epic age (c. 500 BCE–100 CE), things got slightly complicated.

The Mahabharata (Anushasana Parva 115.33) has Bhishma says:

“Non-violence is the highest duty and the highest teaching.”

Yet the same text also shows the Pandavas hunting and eating meat in the forest during their exile (Vana Parva). Draupadi herself cooks venison (originally meant the meat of a game animal but now refers primarily to the meat of deer) for the brothers. The contradictions are evident.

In the Valmiki Ramayana (Ayodhya Kanda 20.29), Rama tells Bharata:

“Like a bull fed on grass, I shall live in the forest, eating roots and fruits, and sometimes meat.”

Although later versions edited or interpreted such verses metaphorically, early renderings suggest that meat-eating, even by the divine, wasn’t taboo.

Jain and Buddhist Intervention: Ahimsa Crashes the Party

Enter Mahavira and Buddha around the 6th century BCE—the original ethical vegetarians.

The Jains completely banned meat consumption, as Ahimsa (non-violence) was central to their faith. Buddhism, meanwhile, allowed meat but only if the monk did not see, hear, or suspect that the animal was killed for him (Jivaka Sutta, Majjhima Nikaya 55).

These movements deeply influenced Hindu thought. The Upanishads, written around this time, began emphasizing inner purity and non-violence. For example, the Chandogya Upanishad (8.15.1) recommends a sattvic (pure, vegetarian) diet for spiritual seekers.

Later, the Manusmriti (5.51–56) goes so far as to declare:

“One should abstain from eating all kinds of meat… the eater of meat is the greatest of sinners.”

Though Manu still allows meat during sacrificial rituals, the general mood was shifting toward restraint.

Medieval Makeover: Brahmins, Bhakti, and a New Food Code

By the Gupta period (4th–6th century CE), vegetarianism had gone mainstream—especially among the Brahmin elite. Abstaining from meat became a symbol of spiritual refinement and caste superiority.

The Bhagavad Gita (17.7-10) classifies food into three types:

- Sattvic (pure): fresh, vegetarian, calming

- Rajasic (stimulating): spicy, salty, etc.

- Tamasic (stale, meat, intoxicants): linked with ignorance and suffering

Bhakti saints like Tulsidas and Chaitanya Mahaprabhu further championed vegetarianism, tying food with devotional purity.

Yet, as always, Hinduism’s culinary code remained flexible:

- Tantric traditions in Kashmir and Bengal included meat, alcohol, and even sexual rites.

- Bengali Brahmins famously justified fish-eating by calling it “jal-taru” (water vegetable).

- Rajputs, Kshatriyas by class, proudly ate meat as a warrior tradition.

- Hinduism had a rulebook—but always kept an appendix for exceptions.

Colonial Confusion: How the British Rewrote the Menu

Then came the British. Armed with Orientalist stereotypes, they portrayed Hindus as cow-worshipping vegetarians—gentle, spiritual, and passive (in contrast to the ‘beef-eating, ruling’ Muslims).

This version served colonial interests and was readily adopted by 19th-century Hindu reformers like Dayananda Saraswati and the Arya Samaj, who wanted to purify Hinduism of “degenerate” customs and align it with Victorian ideals.

The cow, once sacrificed in ancient rituals, was rebranded as Gaumata, a divine symbol of non-violence. Cow protection became a nationalist cause.

Vegetarianism, now fused with identity politics, became a way to distinguish “pure” Hindus from others. And here we are today—debating biryani bans while citing 3,000-year-old scriptures.

Final Bite: Meat Was Never the Problem. Politics Is.

So the next time someone insists that Hindus have always been vegetarian, remind them that:

- The Rigveda had beef recipes.

- Rama ate meat.

- Bhakti saints fasted while Rajputs feasted.

- Tantrics partied like it was 999 CE.

Hinduism’s relationship with food has always been rich, diverse, and yes—contradictory. What’s changed is not the diet, but how we weaponize it.

Because it’s easier to police someone’s plate than to grapple with India’s messy, glorious, pluralistic past.