During the times of the pandemic, for many people who have witnessed the tremendous growth of medical science and healthcare, in general, it is very difficult to understand why developing a vaccine for COVID-19 is taking so long.

Also, given the fact that developing the vaccine for COVID-19 must be on the top of the must-to-do list among the top scientists across the world. There is no lack of funding or manpower either, everyone must be working in the same direction.

To understand why, even with global efforts, it might take this long, you will have to understand how the process of vaccine development works.

Understanding the process of vaccine development

As the starting point, one should know that vaccine development is a long, complex process, historically it often took 5-10 years and a high-level collaboration between private and government organizations.

Collaboration among private and government organizations wouldn’t be the problem this time. Yet, for example in the case of Ebola, the vaccine development took more than 5 years to get approved.

Vaccines are developed, tested, and regulated in a very similar manner to other drugs. However, vaccines are even more thoroughly tested than non-vaccine drugs because the number of human subjects in vaccine clinical trials tends to be much higher.

You may also like: WHO Warns Against Immunity Passports ‘Could Increase Virus Spread’

Stages of Vaccine Development and Testing

In most countries including the United States, vaccine development and testing follow a standard set of steps. However, they can vary from country to country.

The first stages are exploratory in nature. Regulation and oversight increase as the candidate vaccine makes its way through the process.

1. Exploratory Stage

This stage involves basic laboratory research and often lasts 2-4 years. Government-funded academic and governmental scientists identify natural or synthetic antigens that might help prevent or treat a disease.

These antigens could include virus-like particles, weakened viruses or bacteria, weakened bacterial toxins, or other substances derived from pathogens.

2. Pre-Clinical Stage

Pre-clinical studies use tissue-culture or cell-culture systems and animal testing to assess the safety of the candidate vaccine and its immunogenicity, or ability to provoke an immune response.

Animal subjects may include mice and monkeys. These studies provide researchers with an idea of the cellular responses they might expect in humans.

They may also suggest a safe starting dose for the next phase of research as well as a safe method of administering the vaccine.

Researchers may adapt the candidate vaccine during the pre-clinical state to try to make it more effective.

They may also do challenge studies with the animals, signifying that they vaccinate the animals and then try to infect them with the target pathogen.

Sadly, many candidate vaccines never advance beyond this stage because they fail to generate the desired immune response.

This pre-clinical stages usually last 1-2 years and usually involves researchers in private industry.

3. IND Application

A sponsor, usually a private company, submits an application for an Investigational New Drug (IND) to the regulatory authority of a country.

The sponsor details the manufacturing and testing processes summarize the laboratory reports and describe the proposed study. An institutional review board, representing an institution where the clinical trial will be conducted, must approve the clinical protocol.

Once the IND application has been approved, the vaccine is subject to three phases of testing.

However, with COVID-19 vaccine development, we have been able to compensate for the above three stages. The challenge remains with the next stage which is ‘Clinical Studies with Human Subjects’.

Most scientists believe that this stage can be shortened but can’t be drastically reduced as has happened with the above two stages.

4. Clinical Studies with Human Subjects

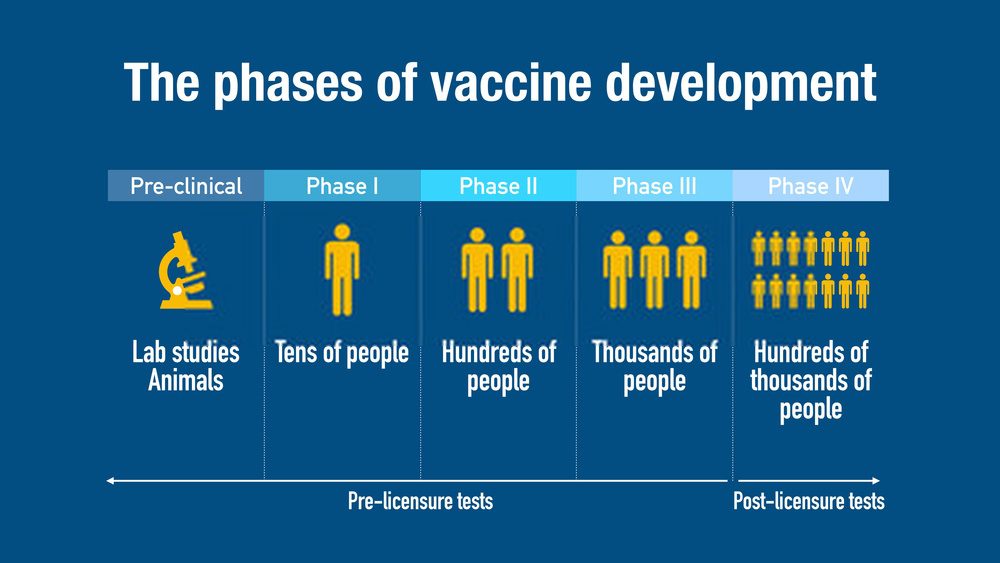

The clinical studies with human subjects usually have 3 phases, but can have the option phase 4. There are many countries right now that have expedited the process of vaccine development and are currently at the beginning of clinical studies with Human.

It is this stage that takes the real chunk of time. To understand this you need to consider that vaccines like diseases have different effects on different individuals.

Some individuals may also have side effects, therefore it becomes necessary to observe the subject for a longer duration of time to see if any side-effects show after a given interval of time.

Also, you need to cover for the variations in the population. You must have the trials covering enough people to represent the whole population by extrapolation.

This essentially means that you will have to cover all age groups, ethnicity, co-morbidities, risk-profile, gender and much more.

Phase I Vaccine Trials

This first effort to evaluate the candidate vaccine in humans includes a small group of adults, usually between 20-80 subjects. If the vaccine is intended for children, researchers will first test adults, and then gradually step down the age of the test subjects until they reach their target.

Phase I trials may be non-blinded (also known as open-label in that the researchers and perhaps subjects know whether a vaccine or placebo is used).

The goals of Phase 1 testing are to assess the safety of the candidate vaccine and to determine the type and extent of the immune response that the vaccine provokes.

In a small minority of Phase 1 vaccine trials, researchers may use the challenge model, attempting to infect participants with the pathogen after the experimental group has been vaccinated.

The participants in these studies are carefully monitored and conditions are carefully controlled. In some cases, an attenuated, or modified, version of the pathogen is used for the challenge.

A promising Phase 1 trial will progress to the next stage.

You may also like:10 Ways COVID-19 Pandemic Will Change Our Lives, forever

Phase II Vaccine Trials

A larger group of several hundred individuals participates in Phase II testing. Some of the individuals may belong to groups at risk of acquiring the disease.

These trials are randomized and well-controlled and include a placebo group.

The goals of Phase II testing are to study the candidate vaccine’s safety, immunogenicity, proposed doses, schedule of immunizations, and method of delivery.

Phase III Vaccine Trials

Successful Phase II candidate vaccines move on to larger trials, involving thousands to tens of thousands of people.

These Phase III tests are randomized and double-blind and involve the experimental vaccine being tested against a placebo (the placebo may be a saline solution, a vaccine for another disease, or some other substance).

One Phase III goal is to assess vaccine safety in a large group of people. Certain rare side effects might not surface in the smaller groups of subjects tested in earlier phases.

For example, suppose that an adverse event related to a candidate vaccine might occur in 1 of every 10,000 people. To detect a significant difference for a low-frequency event, the trial would have to include 60,000 subjects, half of them in the control, or no vaccine, group.

Next Steps: Approval and Licensure

After a successful Phase III trial, the vaccine developer will submit a Biologics License Application to the regulatory authority of the country. They will inspect the factory where the vaccine will be made and approve the labelling of the vaccine.

After licensure, the regulatory authority for e.g in the US FDA — will continue to monitor the production of the vaccine, including examining facilities and reviewing the manufacturer’s tests of lots of vaccines for potency, safety and purity.

The FDA has the right to conduct its own testing of manufacturers’ vaccines.

You may also like: Coronavirus Live Tracker

Post-Licensure Monitoring of Vaccines

A range of systems monitors vaccines after they have been approved. They include Phase IV trials, the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, and the Vaccine Safety Datalink.

Phase IV Trials

Phase IV trials are optional studies that drug companies may conduct after a vaccine is released. The manufacturer may continue to test the vaccine for safety, efficacy, and other potential uses.

How the vaccine development will look like for COVID-19

The prevailing system for developing, testing, and regulating vaccines was developed during the 20th century as the groups involved standardized their procedures and regulations.

China shared publicly the full RNA sequence of the virus — now known as SARS-CoV-2 rather than COVID-19, which refers to the disease itself — in the first half of January.

This kickstarted efforts to develop vaccines around the world, including at the University of Queensland and institutions in the US and Europe.

By late January, the virus was successfully grown outside China for the first time, by Melbourne’s Doherty Institute, a critically important step. For the first time, researchers in other countries had access to a live sample of the virus.

Using this sample, researchers at CSIRO‘s high-containment facility (the Australian Animal Health Laboratory) in Geelong, could begin to understand the characteristics of the virus, another crucial step in the global effort towards developing a vaccine.

Vaccines have historically taken two to five years to develop. But with a global effort, and learning from past efforts to develop coronavirus vaccines (read SARS), researchers could likely develop a vaccine in a much shorter time.

Moreover, no single institution has the capacity or facilities to develop a vaccine by itself. As you have seen, there are more stages to the process than many people appreciate.

Moreover, each of these steps in the vaccine development process faces potential challenges.

[COVID19-SLIP country=”India” covid_title=”Coronavirus” confirmed_title=”Confirmed” deaths_title=”Deaths” recovered_title=”Recovered” active_title=”Active” today_title=”24h” world_title=”World”]

Here are some of the challenges we face in developing a vaccine for SARS-CoV-2.

Our previous work with SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) has given us a good foundation to build on.

SARS is another member of the coronavirus family that spread during 2002-03. Our scientists developed a biological model for SARS, using ferrets, in work to identify the original host of the virus– bats.

SARS and the new SARS-CoV-2 share about 80-90 percent of their genetic code. So our experience with SARS means we are optimistic our existing ferret model can be used as a starting point for work on the novel coronavirus.

What will happen to vaccine development if the virus mutates?

Most scientists agree that there is a strong possibility that SARS-CoV-2 will continue to mutate.

Being an animal virus, it has already likely mutated as it adapted — first to another animal and then jumping from an animal to humans.

Initially, this was without transmission among people, but now it has taken the significant step of sustained human-to-human transmission.

As the virus continues to infect more people, it is going through something of a stabilization, which is part of the mutation process.

This mutation process may even vary in different parts of the world, for various reasons.

This includes population density, which influences the number of people infected and how many opportunities the virus has to mutate.

Prior exposure to other coronaviruses may also influence the population’s susceptibility to infection, which may result in variant strains emerging, much like seasonal influenza.

Therefore, it’s crucial we continue to work with one of the latest versions of the virus to give a vaccine the greatest chance of being effective.

Other challenges ahead

Another challenge is manufacturing proteins from the virus needed to develop potential vaccines. These proteins are uniquely designed to evoke an immune response when administered, allowing a person’s immune system to defend against future infection.

Luckily, recent advances in understanding viral proteins, their structure, and functions, has supported this work to progress around the world with significant momentum.

Developing a vaccine is an enormous task and not something that can happen overnight. But if things go to plan, it will be much faster than we’ve seen before.

So many lessons were learned during the SARS outbreak. And the knowledge the global scientific community obtained from trying to develop a vaccine against SARS has given us a good head-start on developing one for this virus.