Antonie Philips van Leeuwenhoek, the father of microbiology, was horrified by the appearance of sperm under the microscope.

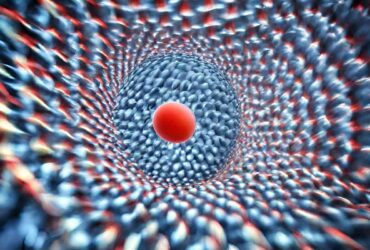

Even though human civilization had a good understanding of reproduction prior to the invention of the microscope, it wasn’t until the 17th century that anyone knew what sperm actually were or had seen their distinctive appearance.

Antonie Philips van Leeuwenhoek, the father of microbiology, was spooked by the discovery of sperm and wished he could erase the image from his memory.

The invention of the microscope

The microscope was invented in the early 17th century by Dutch scientist Antonie Philips van Leeuwenhoek. Thus he became the first person to observe and describe microorganisms, which he called “animalcules,” using a simple microscope that he had made himself.

He is often referred to as the “father of microbiology” because of his pioneering work in this field. Van Leeuwenhoek’s discoveries revolutionized our understanding of the microscopic world and paved the way for future advances in the field of biology.

When Royal Society Secretary Henry Oldenburg asked Leeuwenhoek to examine the microscopic semen, the Dutch draper initially did not reply “because he felt it was ‘unseemly.'”

Despite living in the Dutch Republic during the 17th century, Leeuwenhoek’s story could be mistaken for personifying the American Dream.

Although he did not have formal scientific training, Van Leeuwenhoek possessed a natural intelligence and strong work ethic that allowed him to make substantial contributions to the field of science.

Armed with those tools, Leeuwenhoek made discoveries that transformed how human beings view the world.

By the end of his life, he was a prosperous pillar of his community and regarded throughout the West as an intellectual giant.

He owed all of this to one single instrument that opened a whole new world to humanity — his cutting-edge microscopes and their ability to study “animalcules,” as bacteria were then called.

His microscopes clearly established this startling fact to humanity that it has always shared this planet with innumerable single-celled organisms.

Yet when Leeuwenhoek discovered sperm, he anticipated that the world would be disgusted.

Life of Leeuwenhoek

Antonie Philips van Leeuwenhoek was born in 1632 to a well-to-do family in Delft, a small town in the Netherlands where he would spend most of his life.

As a draper, van Leeuwenhoek sold cloth to merchants for use in clothing, but he became frustrated with the limitations of existing lenses, which were not powerful enough to see threads clearly.

In response, van Leeuwenhoek designed his own strong lenses and employed them to create single-lens microscopes.

In 1673, he became the first scientist to intentionally interact with the microbiological world using these microscopes, discovering bacteria and conducting scientific experiments.

Interactions with the Royal Society and hesitation to examine semen

Van Leeuwenhoek never wrote any books, but he communicated his findings through letters published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.

These letters were widely read and admired by educated Europeans, as van Leeuwenhoek used his microscope to study a variety of organisms including bee stingers, human lice, and lake microbes.

However, van Leeuwenhoek was hesitant to examine semen due to his religious beliefs. Despite this reluctance, he eventually gave in to the pressure to study it in 1677.

His reaction can be best understood by what he wrote to the Royal Society about what he saw.

“If your Lordship should consider that these observations may disgust or scandalize the learned, I earnestly beg your Lordship to regard them as private and to publish or destroy them as your Lordship sees fit.”

“Without being snotty, Leeuwenhoek (the ‘van’ is an affectation he adopted later on) was not trained as an experimental thinker,” explained Matthew Cobb, a British zoologist and author of the book “Generation: The Seventeeth Century Scientists Who Unraveled the Secrets of Sex, Life, and Growth.”

Cobb recalled that when Royal Society Secretary Henry Oldenburg asked Leeuwenhoek to look at semen, the Dutch draper initially did not reply “because he felt it was ‘unseemly.'”

Even though he eventually overcame his reservations, Leeuwenhoek added so many caveats to his semen research that it is clear he remained somewhat uncomfortable.

A few months later, he wrote the letter as mentioned above saying that he would not mind if his discovery was suppressed.

“He reassured the Royal Society that he had not obtained the sample by any ‘sinful contrivance’ but by ‘the excess which Nature provided me in my conjugal relations,'” Cobb explained. “He wrote that a mere ‘six heartbeats’ after ejaculation, he found a vast number of living animalcules.”

A few months later, he wrote the letter mentioned above saying that he would not at all mind if his discovery was suppressed. After all, in addition to being grossed out, Leeuwenhoek was not under the impression that he had found anything special.

“He was initially not particularly interested in the ‘animalcules’ as he called them — he assumed they were just another form of life, just like the stuff he saw in the water, or from between his teeth,” Cobb pointed out.

“Then he got interested in some odd fibrous structures that he could see, and considered that they were of some interest.”

The “odd fibrous structures” were, of course, the sperm tails. While Leeuwenhoek could never have imagined this at the time, the cells that he had spotted are unlike anything else in the human body.

As Syracuse University biologist Scott Pitnick has pointed out, sperm cells are the only human cells designed to perform functions outside of the actual body.

They must undergo radical physical changes as they undertake their journey from the testes through the complex female reproductive tract. Even today, scientists “understand almost nothing about sperm function, what sperm do,” Pitnick told Smithsonian Magazine.

This context is crucial in understanding why Leeuwenhoek initially assumed sperm were nothing special. In the early 21st century, it is common knowledge that humans are created when a sperm fertilizes an egg, but in the 17th century, such a concept was difficult to imagine.

“He did not conclude that the animalcules were involved in producing babies,” Cobb wrote to Salon, adding that the term “spermatozoa” was not even coined until the 1820s, and by a man who classified them as part of a group of parasitic worms.

Yet despite (or perhaps because of) the lack of clarity on what these “animalcules” even were, Leeuwenhoek’s supporters at the Royal Society wanted him to continue studying them.

As it turned out, at least some of Leeuwenhoek’s acquaintances in Delft shared his unique inhibitions about male bodily fluids.

“A medical student acquaintance, Ham, said that his ‘friend’ had lain with an ‘unclean woman’ and had a discharge,” Cobb wrote to Salon. “Ham looked at the discharge from his ‘friend’ and saw animalcules in it (the modern consensus is that the ‘friend’ had gonorrhea, in which dead spermatozoa can appear in the discharge).

He was not searching intentionally for the secret of life or trying to understand the role of semen, and his discovery did not lead to any breakthrough in this respect. That lay about 170 years in the future!”

By contrast, sperm would remain mostly a mystery in Leeuwenhoek’s own lifetime. After telling Leeuwenhoek to make more observations, the Royal Society finally published his paper in Latin in 1679.

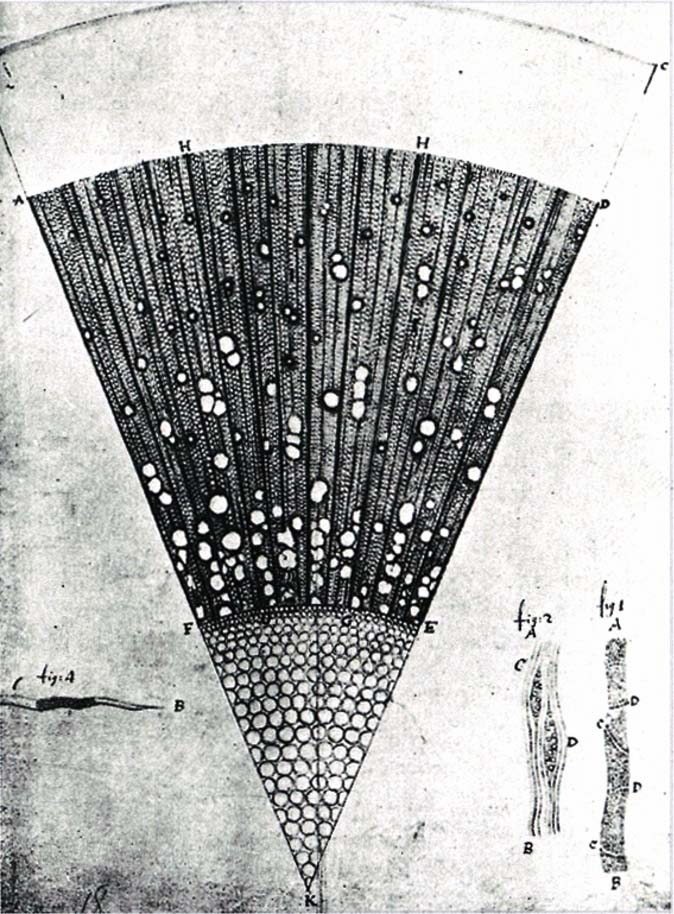

It included illustrations of the “animalcules” from not only human semen but also the semen of dogs, horses, and rabbits.

“The Royal Society was not particularly impressed — it didn’t discuss the issue until July 1679,” Cobb told Salon. “Other thinkers were sharper and suggested that this might shed light on ‘generation’ — where babies come from. But it wasn’t clear to anyone what it actually proved.”

For his part, “Leeuwenhoek finally decided that these animalcules were the sole source of life, with eggs either being non-existent (mammals) or sources of food (birds, frogs, etc.) but he had no proof, and his view was very much a minority one for the next two centuries.”

At the same time, Leeuwenhoek mostly continued with his career as a draper and a world-renowned expert on developing microscopes. Because he did not fully understand what he had seen, the world would view his discovery as little more than a gross piece of trivia for a few more centuries.

Leave a Reply