Maharishi Kanad (also known as Kanada or Kanada Maharishi) was an ancient Indian philosopher and founder of the Vaisheshika school of Hindu philosophy.

He is known for his treatise on natural philosophy, the Vaisheshika Sutras, which deals with topics such as atomic theory, the nature of the universe, and the concept of causation.

His philosophical ideas have influenced many other schools of Indian philosophy, including Nyaya and Yoga. He is considered one of the most important figures in the history of Indian philosophy.

Many regard him as a scientist from ancient India, as his philosophies touch upon many aspects that fall under the purview of modern science. It is without question that he was one of the greatest philosophers not only in India, but also in the world.

However, some believe that he hasn’t been given due credit for his atomic theory and Dalton, born thousands of year later, was instead named the father of modern atomic theory. They attribute it to some western bias and neglect for scientific endeavors of ancient India.

As Maharishi Kanad was a Hindu sage, this topic involves some religious overtone too. This is where we decided to decode the topic of credit of Atomic Theory and bring about information that anyone who tries to understand with a logical and scientific temper will be able to understand.

[rb_related title=”You May Also Like” total=”4″ style=”dark” ids=”13409,7427,11550,1157″]

Maharishi Kanad’s atomic theory

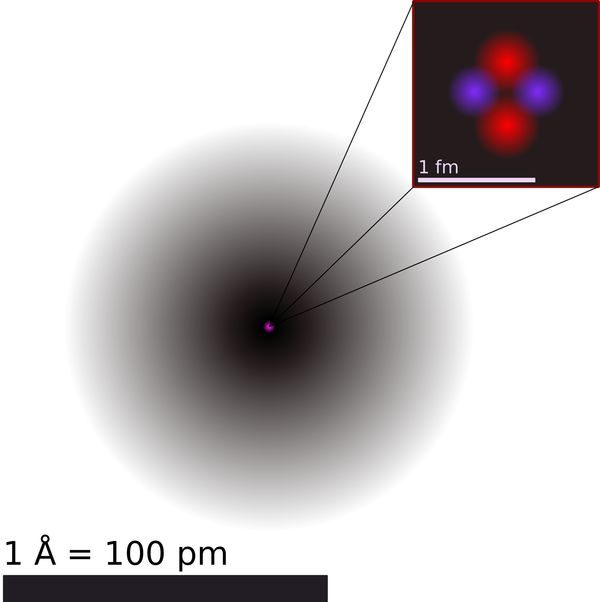

Maharishi Kanad is known for his philosophical atomic theory, which is outlined in his treatise on natural philosophy, the Vaisheshika Sutras. According to this theory, all matter is made up of tiny indivisible particles called atoms, which are eternal and indestructible.

These atoms combine in various ways to form the objects and substances that we see in the world around us.

The properties of an object or substance are determined by the type and number of atoms it is made up of, as well as the arrangement of these atoms.

Maharishi Kanad’s theory is one of the earliest known examples of atomic thought in ancient Indian philosophy.

The Vaisheshika Sutras, authored by him is a major work of Indian philosophy that also explores the nature of the universe and the fundamental principles of reality.

The text is organized into ten chapters, or Adhyayas, which cover a wide range of topics including the nature of atoms, the concept of causation, and the properties of matter.

The Vaisheshika Sutras is known for its systematic and logical approach to these topics, and its influence can be seen in many other schools of Indian philosophy.

The text has been studied and commented on by many philosophical scholars and remains an important source of information on the philosophical thought of ancient India.

The Vaisheshika Sutras is one of the six classical Indian philosophical texts known as the Vedangas, and is considered one of the most important works in the field of Indian philosophy. His discoveries fall into a class which is now known as Philosophical atomism. We need to further understand this term to address the issue of credit for atomic theory.

Philosophical Atomism

The idea that matter is made up of discrete units is a very old idea, appearing in many ancient cultures such as ancient Greece — and as we already discussed in India — by Maharishi Kanad, estimated to have lived sometime between the 6th century to 2nd century BCE, little is known about his life.

What is clearly known is that word “atom” (Greek: Atomos), meaning “uncuttable”, was coined by the Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher Leucippus and his pupil Democritus (460–370 BCE).

Democritus taught that atoms were infinite in number, uncreated, and eternal and that the qualities of an object result from the kind of atoms that compose it.

Democritus’s atomism was refined and elaborated by the later Greek philosopher Epicurus (341–270 BCE), and by the Roman Epicurean poet Lucretius (99–55 BCE).

During the Early Middle Ages, atomism was mostly forgotten in western Europe. During the 12th century, it became known again in western Europe through references to it in the newly-rediscovered writings of Aristotle.

The opposing view of matter upheld by Aristotle was that matter was continuous and infinite and could be subdivided without limit.

In the 14th century, the rediscovery of major works describing atomist teachings, including Lucretius’s De rerum natura and Diogenes Laërtius’s Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, led to increased scholarly attention on the subject.

Nevertheless, because atomism was associated with the philosophy of Epicureanism, which contradicted orthodox Christian teachings, belief in atoms was not considered acceptable by most European philosophers.

The French Catholic priest Pierre Gassendi (1592–1655 CE) revived Epicurean atomism with modifications, arguing that atoms were created by God and, though extremely numerous, are not infinite. He was the first person who used the term “molecule” to describe the aggregation of atoms.

Gassendi’s modified theory of atoms was popularized in France by the physician François Bernier (1620–1688 CE) and in England by the natural philosopher Walter Charleton (1619–1707 CE).

The chemist Robert Boyle (1627–1691) and the physicist Isaac Newton (1642–1727) both defended atomism and, by the end of the 17th century, it had become accepted by portions of the scientific community.

The concept of indivisible atom has been widespread across different cultures and was even generally accepted by scientific community. The earliest mention could be either Democritus (460–370 BCE) or Maharishi Kanad (6th century to 2nd century BCE).

The question therefore arise, why aren’t they given credit for the atomic theory? For this one needs to understand that philosophy or proposing is idea of atom is very different from scientific atomic theory.

Scientific Atomic Theory

It is John Dalton, who is credited with developing the modern atomic theory, which is similar to same fundamental principles as the atomic theory of Maharishi Kanad. Dalton’s atomic theory was developed in the early 19th century and was most importantly, the first to be supported by experimental evidence.

It introduced several important concepts, such as the idea that atoms are indivisible and indestructible, and that they combine in whole-number ratios to form compounds.

Dalton’s atomic theory was a major breakthrough in the field of chemistry and laid the foundation for the development of modern atomic theory. While Maharishi Kanad’s atomic theory predates Dalton’s by several centuries, Dalton’s theory is considered the more significant and influential of the two.

Kanad’s posited on the idea of the atom did not carry an explanatory burden — it was just a speculative thesis. It is not logical to compare it with modern atomic theories.

It’s useful to understand the doctrine of Vaisheshik in brief in relation to the nature of the atom to see if there could be any scientific aspects to it.

Vaisheshik Darshan is one of the six schools of orthodox philosophy (the others being nyaya, samkhya, yoga, mimamsa and vedanta).

Traditionally, scholars have studied Indian philosophy under these six schools, considered to be six ‘systems’ of philosophy by Max Müller and others.

The study of philosophy often includes the sub-discipline of metaphysics, which is concerned with the fundamental nature of reality. In the context of Indian philosophy, the topics covered by the Vaisheshika school, such as the nature of atoms and causation, would typically be considered part of metaphysics.

A standard textbook on Indian philosophy would likely include a section on the Vaisheshika school under the heading of “metaphysics”.

Furthermore, Vaisheshik’s metaphysics recognizes seven categories, and Dravya (substance itself) is one of them. Substances further come under two heads, the eternal and the non-eternal.

There are nine kinds of eternal substance as per the texts:

- Prithvi (earth)

- Jala (water)

- Tejas (fire)

- Vayu (air)

- Akasha (ether)

- Kala (time)

- Dik (space)

- Atma(soul)

- Manas (mind).

These eternal substances are not day-to-day concrete objects that can be experienced. Earth, water, fire, and air can be considered to be principles or essences that can’t be experienced, and it is only these four eternal substances that contain atoms.

The doctrine also makes it very clear that these atoms are not perceivable but are to be inferred, although the principle of inference is not clear.

As a result, it would be more appropriate to say that it’s not an inference that plays any part here but some kind of speculation. For inference to be involved, there ought to be something that is empirical that it should offer an explanation for.

But if the substances are not objects of experience, then there is nothing empirical at play. The sages simply put forth the view that the atoms of these substances are the smallest elements that are without parts (i.e. indivisible) and that are, in themselves, motionless.

The movement of atoms, according to them, is caused by the unseen agency residing in individual souls.

Can such a doctrine that is not connected to anything empirical be called scientific? Science (as we conduct it today) is essentially empirical.

The real Atomic Theory

Atomic theory is the scientific theory that explains the nature of matter at the atomic level. According to this theory, all matter is composed of tiny particles called atoms, which are the fundamental building blocks of the universe.

The concept of atoms can be traced back to the ancient philosophy of atomism by Greek Philosophers, which held that all matter is composed of indivisible particles.

In the early 1800s, John Dalton’s observations of chemical reactions led to the development of his atomic theory, which proposed that atoms were the fundamental units of matter.

This theory was later supported by the kinetic theory of gases and the proof of Brownian motion. Today, atomic theory is an essential part of chemistry and physics.

Although atomic theory in science is considered to have originated with John Dalton (1766-1844), the English physicist and chemist. Though the early Greek philosophers, like Leucippus of Miletus and Democritus of Abdera, did posit atoms in their philosophies, one never considers them to be scientific.

The starting point of Dalton’s atomic hypothesis was also substance – but the substances of Dalton are chemical kinds that are objects of experience in contrast to that of the Vaisheshik.

The aim of the chemist was to discover the processes through which different kinds of substances reacted and produced other substances.

Most importantly, it was through Empirical study that he discovered that they reacted in certain proportions by volume or by weight – whether as solids, liquids, or gases.

The ratios of these reacting substances were always in whole numbers. A law of constant proportion was subsequently formulated.

The law of constant proportion states that a chemical compound always contains the same elements in the same proportions by weight. This means that if you were to take two samples of the same compound, no matter how big or small, and weigh the elements they are made of, you would always get the same ratio.

For example, if you had a compound made of hydrogen and oxygen, and you weighed the hydrogen and oxygen in one sample, you would always find that there are twice as many hydrogen atoms as oxygen atoms, no matter how much of the compound you have. This is because the atoms in a compound are always arranged in a specific, fixed ratio.

Dalton’s explanation for this was that substances or matter were composed of atoms and that during a reaction, the atoms of these substances combined to form clusters of molecules.

In all, this was an experimental discovery and, in this sense, an empirical discovery.

Of course, the atomic theory of today is substantially different from that of Dalton’s but the point is that Dalton’s was considered to be the first scientific theory of atoms. Why? Because it was attempting to rationally explain an empirical law.

One of the arguments that could be given by the advocates of the so-called ‘Kanad’s atomic theory is that Dalton’s theory was rejected by the evolving standards of scientific investigation.

Indeed, the nature of science is to remain open to modifications, but the advancement of scientific theories lies in more empirical findings made possible by advancements in technology and theoretical knowledge. In its essence, science has to be empirical. Kanad’s atomic doctrine is not.

It doesn’t take anything away from the achievements of Kanad. For example, Aristotle’s contribution can’t be compared with Newton, both have a special place in their contribution to humanity. At the same time the idea that Kanad has been denied his due credit is not correct.