The first case of the COVID-19 pandemic in India was reported on 30 January 2020. Since then, the outbreak has spread across the nation, with more than 85,000 cases and over 2,700 deaths.

India has just surpassed the number of cases of novel coronavirus reported by China where the virus originated. Already running into the end of the third phase of the most strict lockdown imposed by any country in the world, the way ahead for India doesn’t look easy.

First was the great sufferings of the migrant workers from various other states in India who were stuck with sudden lockdown imposed by the government. Many had no other options but to walk home for distances that ran from several hundred kilometers to even reaching thousand.

What followed then, was a never seen before slowdown of the economic activity. Many believe that the prompt lockdown imposed by the government was a correct move and has slowed down the spread of the virus. What does the data say?

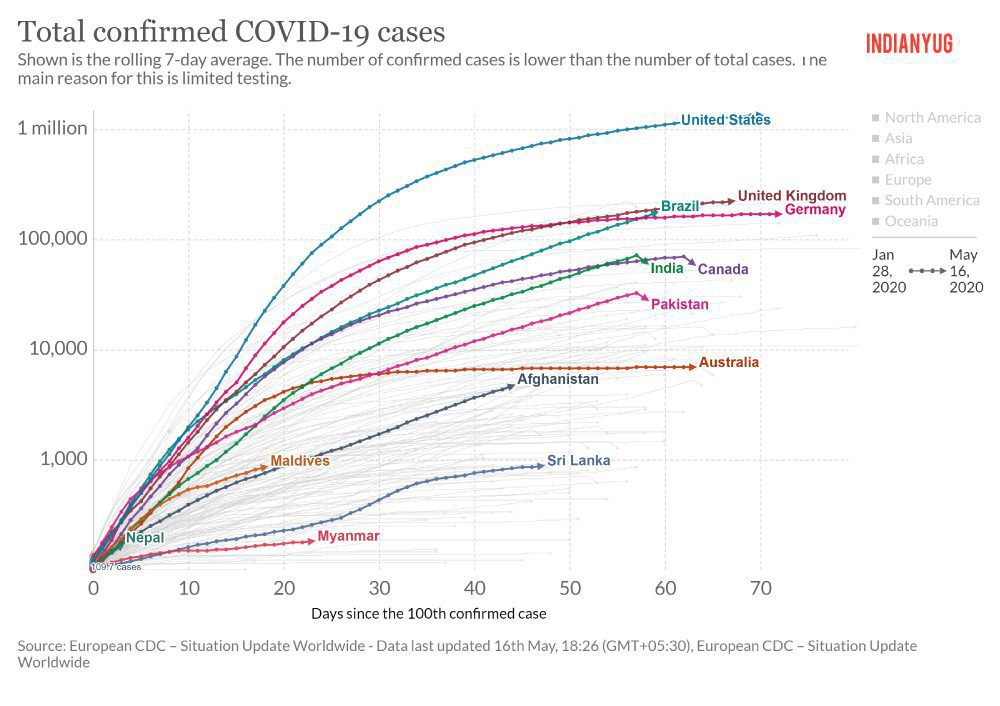

This is a logarithmic graph of the total number of cases for India vs other countries. For comparison, neighboring nations of Nepal, Pakistan, Afganistan, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar are included.

At this point in time, all of them seem to be doing better than India with respect to the logarithmic graph of the total number of confirmed cases.

The dates when the virus started spreading vary in different countries, therefore the data plotting starts from the day since the 100th confirmed case in each country.

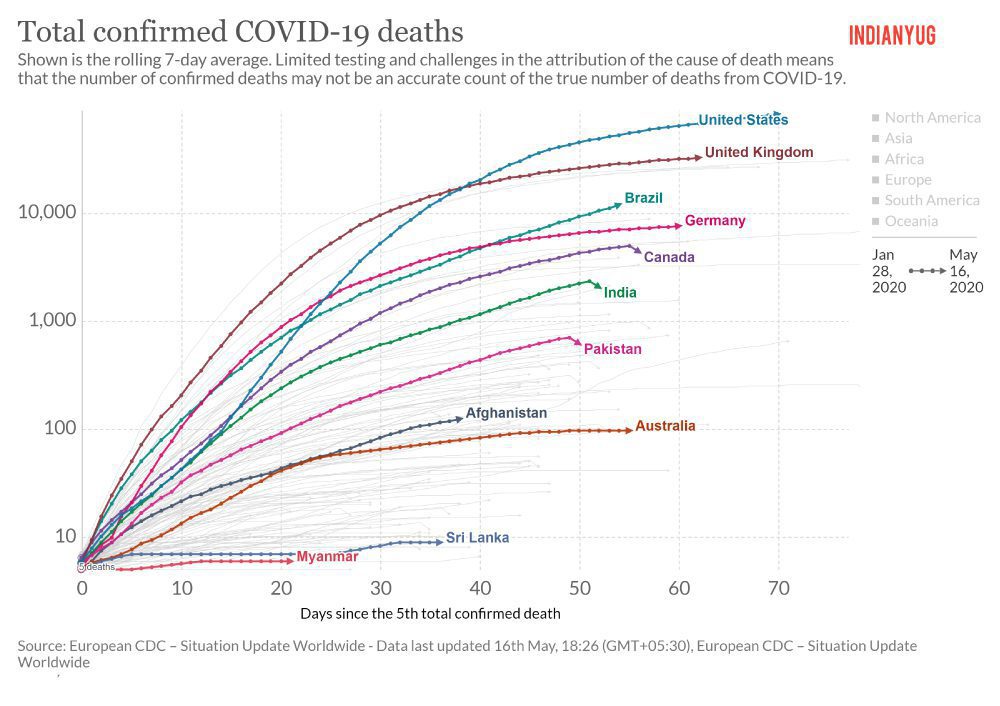

What about the number of deaths? Many observers have pointed out that India is doing better in terms of the death rate. What does the data say?

Here too, India doesn’t seem to be doing better than other neighboring countries. However, it is still doing better than other European and American countries. Please note that the data is based on the confirmed number of reported deaths and cases for all the countries shown in the graph.

At the moment, the curve doesn’t seem to be flattening for India. When considered along with one of the most stringent lockdowns among all the major countries, India certainly doesn’t seem to be doing too well.

To be fair, no government seemed to have a complete idea about how to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic situation in their country. For a populous country like India, none of the choices were easy.

On one hand, there was a huge economic cost, on the other, there was a great danger of pandemic spreading unstopped, crippling the healthcare infrastructure of the country.

You may also Like: Cow and The Story of Origin of Vaccine That Ended Smallpox

What India did get right about the pandemic

For a densely populated country like India, an early lockdown and strict enforcement were necessary. India’s prime minister Modi ordered all 1.3 billion people in the country to stay inside their homes for three weeks starting Wednesday — the biggest and most severe action undertaken anywhere to stop the spread of the coronavirus.

The lockdown was placed on March 25 midnight, when the number of confirmed positive coronavirus cases in India was only around 500. By all accounts, it was a proactive measure that was taken in time to avoid an unrestricted spread of the virus.

This was a decision that most countries in the developed world had shied away from. Some of the problems, notably the physical difficulties of social distancing in overcrowded urban clusters and the consequences of work loss on those who live on the margins, were anticipated.

“What has worked for India is that the timing of the lockdown was pretty good. We locked it down at the beginning of the spread and, hence, that has helped curtail the spread of the virus,” said Oommen C. Kurian, a senior fellow who leads the health initiative at the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) think tank in New Delhi.

Kurian and other experts point to another reason why the early lockdown was key in the fight against COVID-19 — India’s public health care system is skeletal, poorly funded, and has traditionally been neglected.

Government data shows India spent less than 1.3 percent of its GDP on health care in 2017-18, while data collated by How India Lives, an open data repository, reveals that the country had just 61 beds per 100,000 people, on average, before the pandemic.

Combine this with the 48,000 or so ventilators it was estimated to have at that time and you get figures that analysts say were woefully inadequate to meet demand if the number of cases continued to rise.

This eventually led to the authorities scrambling to fix the system.

You may also Like: 10 Ways COVID-19 Pandemic Will Change Our Lives, forever

What India did not get right about the pandemic

Essentially India got the concept of lockdown wrong. Lockdowns are never meant to eventually bring down the number of cases. It typically helps you control the speed of the virus spread, enabling you to implement other measures.

Public health experts like Dr. Amar Jesani, though, believe that the lockdown could have been better utilized. Jesani, a senior public health researcher and editor of the Indian Journal of Medical Ethics, said that the government’s approach seemed to be treating the lockdown as the end, rather than a means to the end.

“A lockdown is not the solution to fight a pandemic. A lockdown is meant to slow the rate of growth of the virus and give the authorities more time to prepare health systems so that they are able to tackle the outbreak when it happens,” he said.

The major challenge with SARS-Cov-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 is that carriers of the virus can be asymptomatic, which means that many carriers can go undetected and still spread the virus.

Testing, treating, and tracking along with the lockdown could have worked better for India. What does the data say about Indian testing for coronavirus?

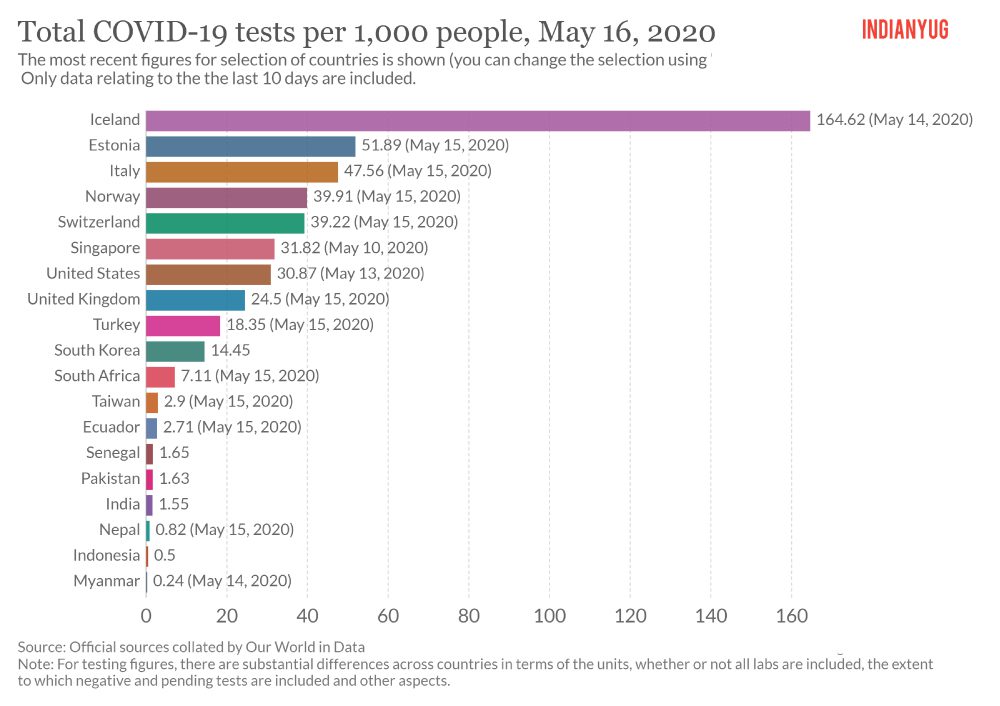

The chart here shows a measure of testing coverage – tests per thousand people. India is fairing below Pakistan in the number of tests per thousand people. In fact, it is among has one of the lowest testing rates in the world.

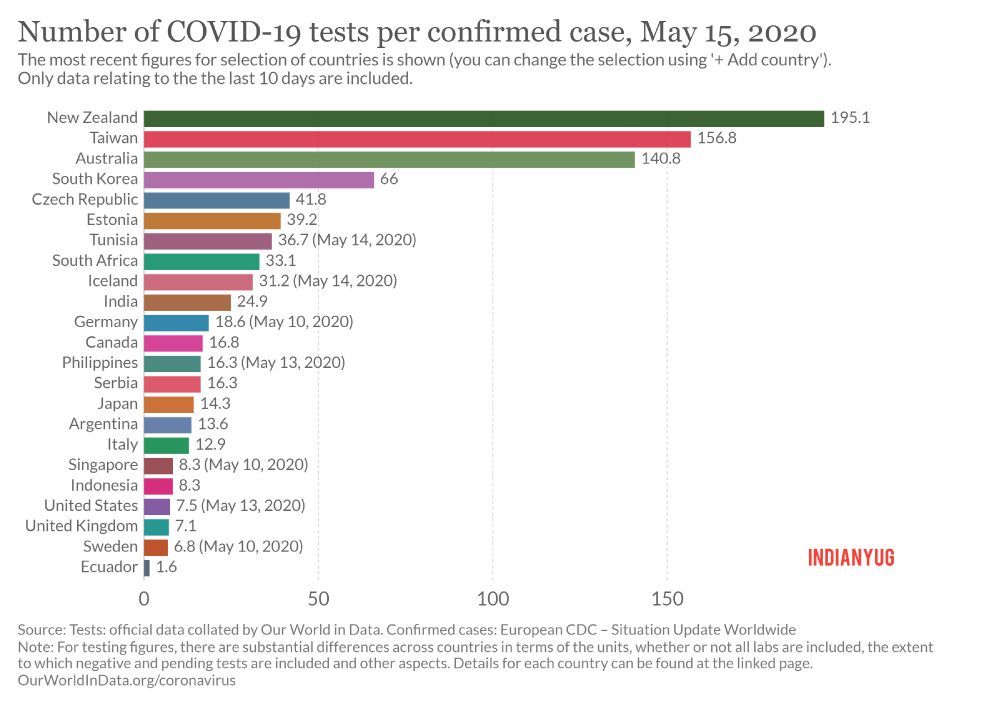

However India is not doing bad on number of COVID-19 test per confirmed case. See below:

At the beginning of an outbreak, where the number of people infected with the virus is low, a much smaller number of tests are needed to accurately assess the spread of the virus.

As the virus infects more people, testing coverage also needs to expand in order to provide a reliable picture of the true number of infected people.

For this reason, it is helpful to look at the number of tests performed for each confirmed case. This gives us an indication of the scale of testing that accounts for the different stages each country may be in its outbreak.

You may also Like: When ‘A Year Without a Summer’ in 1816 Changed the World

Countries are also reporting testing data in different ways — some report the number of tests, others report the number of people tested. This distinction is important – people may be tested many times, and the number of tests a person has is likely to vary across countries.

The data covers the number of persons tested for the virus. This is a more important measure to control the spread of the virus.

Apar from the low testing rate the other aspect where Indian government response to the pandemic seems lacking is — assessing the crisis.

Large crowds of rural migrant workers had gathered at the transport depots in hopes of getting a ride back to their rural villages upon the announcement of the lockdown extension on April 14, and also back when the lockdown was first announced on March 24.

The problem is, whether the government believed that the pandemic will come down below 500 which was the number of cases when the lockdown was first announced, else it was better to allow time for migrant workers to reach their home states when the numbers were still low.

With a large number of cases, the current situation poses a significant risk of contagion and could also spread to the rural areas which have poor access to healthcare.

Furthermore, poor living conditions in many parts of India such as in the shanty towns also put the residents at high risk of contagion despite lockdown measures being in place.

Finally, there is a worry that even the present number of cases in India relative to its large population is likely due to a low testing rate thus far, with cases very likely to surge as testing is increased over time.

India’s unemployment rate has climbed to over 20 percent after the nationwide lockdown implementation, from 6.7 percent just a week before that. This is bases on data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) regarding unemployment

The people of India have already largely been divided into two groups — those who believe the government can do no wrong and those who demand that the right to a COVID-19-free world doesn’t automatically crush on rights and civil liberty.

The lockdown showed that while the rights of some become limited, for others like the laborers it is an existential right connected to their food, dignity, and livelihoods.

Additionally, people who have moved out of cities have also increased the virus’s geographic spread.

Data speaks louder than words, on some fronts India is doing well but not without its share of steps that have gone wrong. It is a long battle for India and the world, where the data will have further stories to tell.