Let’s get one thing clear upfront: India didn’t wake up on 26th January 1950 with a clean slate and a cup of chai. No sir. We woke up with 300 million citizens, thousands of years of cultural baggage, and one angry revolutionary in a suit—Dr. B. R. Ambedkar—who basically said, “We’re not doing this caste supremacy nonsense anymore.”

But someone, somewhere, always whispers: “But Manusmriti said…”

And that, dear reader, is where the real identity crisis begins.

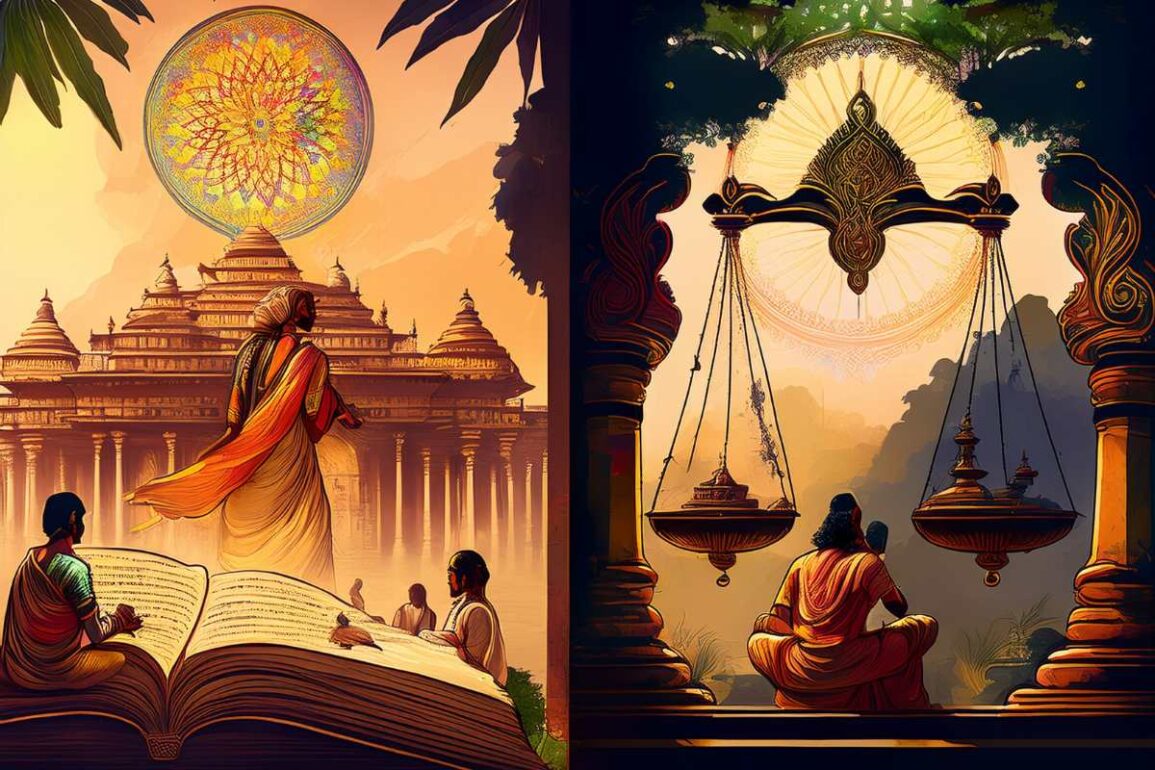

When a 2,000-year-old Brahminical code and a 75-year-old democratic charter walk into the Indian imagination, the result isn’t harmony but a heated national debate. This isn’t a tale of ancient wisdom vs. modernity—it’s about power, morality, and who gets to define what’s right.

What is the Manusmriti?

The Manusmriti, also known as the Manava Dharma Shastra, is an ancient Hindu legal text composed between 200 BCE and 200 CE. It claims to lay down rules for dharma (righteous living), societal structure, and law and has traditionally been attributed to the mythical lawgiver Manu.

But far from being a spiritual guidebook, it’s more like a user manual for a caste-ridden society.

Before the trolls warm up their keyboards, let’s be clear: this is not an attempt to demean the Manusmriti or its place in ancient Indian society. The Manusmriti, like many ancient texts, was a product of its time—a time with rigid hierarchies, limited mobility, and a worldview shaped by survival and order rather than equality and rights.

It served as a code for a particular social structure, and in that context, it had relevance. But just as we’ve moved beyond bloodletting in medicine or geocentric maps in astronomy, we must also evolve past outdated social codes when shaping a modern, democratic nation.

Caste and Social Hierarchy The Manusmriti is unapologetically hierarchical. It assigns duties and rights based on birth, not merit

- “For the prosperity of the world, the Brahmin, the Kshatriya, the Vaishya, and the Shudra were created from the mouth, arms, thighs, and feet of Brahma.” (Manusmriti 1.31)

This cosmic metaphor institutionalizes caste hierarchy. Brahmins were placed at the top and Shudras at the bottom, establishing a social order that lasted for millennia.

Women in Manusmriti When it comes to women, the text is not just outdated; it’s oppressive.

- “Her father protects her in childhood, her husband protects her in youth, and her sons protect her in old age. A woman is never fit for independence.” (Manusmriti 9.3)

This clause underlines Manusmriti’s view that women should remain under male guardianship all their lives. Rights, agency, and freedom? Not in this book.

The Brahminical State The Manusmriti gives ultimate authority to Brahmins:

- “Let the king, after rising early, respectfully attend to Brahmins learned in the three Vedas.” (Manusmriti 7.37)

It envisions a theocratic monarchy led by the priestly class, where secular rule bows to religious diktats. There’s no concept of democracy, individual liberty, or constitutional checks and balances.

Punishments by Caste One of the most disturbing aspects of Manusmriti is its unequal system of justice:

- “If a once-born person insults a twice-born one with gross abuse, he should suffer the cutting off of his tongue; as he is of low origin.” (Manusmriti 8.270)

In this verse, “once-born” typically refers to a Shudra (as they do not undergo the initiation ceremony considered a “second birth”), and “twice-born” refers to the upper three varnas (Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas). The verse prescribes a severe punishment for a Shudra who verbally abuses a member of the higher varnas, explicitly stating the reason as their “low origin”.

Meanwhile, a Brahmin committing the same crime faces a milder penalty or none at all.

Ah yes, the classic defense: “But the caste system was originally based on karma, not janma (birth)! It was about what you do, not who your daddy is.” A noble idea—like communism, or gym memberships in January.

But let’s peek into the texts, shall we? The Bhagavad Gita (Chapter 4, Verse 13) does say, “Chaturvarnyam maya srishtam guna karma vibhagashah”—meaning the four varnas were created by Krishna based on guna (qualities) and karma (work).

Lovely. Spiritual. Flexible. Except… that’s not how it played out. By the time of the Dharmashastras, especially Manusmriti (Chapter 10), caste was very much hereditary.

It even outlined the “punishment” for people born of varna-mixing marriages—like the Shudra father and Brahmin mother combo, whose child, the text charmingly says, becomes a Chandala, condemned to live outside the village, eat from broken pots, and wear clothes from corpses. Not exactly HR policy.

If caste was about the profession, why were children barred from entering the ‘wrong’ job market for millennia? Why were Dalits denied education, temple entry, and even the right to hear sacred verses? Sounds less like a career ladder and more like a caste cage. In theory, varna may have started with some mobility.

But in practice? Birth became destiny—and staying in your “lane” became a religious duty. So next time someone brings up the ancient merit-based caste utopia, feel free to smile and say, “Nice fantasy. Now show me where the application form was for a Brahmin post in 500 BCE.”

Let’s talk about the great Indian epics—Ramayana and Mahabharata—often cited as moral blueprints for society, yet both offer enough caste cringe to make a modern-day HR department sweat bullets. Take Ramayana, for starters. In the Uttara Kanda (the controversial last chapter), we meet Shambuka, a Shudra daring to perform tapasya—a spiritual practice reserved for higher varnas. What does Lord Ram do? He beheads him.

Not metaphorically. Literally. Why? Because a lower-caste man meditating was apparently upsetting the cosmic order. Ah yes, dharma in action—unless you happen to be born into the wrong social bracket. Fast-forward to Mahabharata, where Karna, the tragic hero with the resume of a Kshatriya but the birth certificate of a Suta (charioteer caste), is denied the right to duel Arjuna simply because of his low birth.

Never mind his skills—meritocracy clearly wasn’t trending in ancient Kurukshetra. And then there’s Ekalavya, the forest-dwelling prince of the Nishadas, who is so good at archery that Dronacharya demands his thumb as tuition fees… for a class he wasn’t even allowed to attend.

If that’s not caste-based academic gatekeeping, what is? So, while these epics are often held up as beacons of dharma and virtue, let’s not pretend they were caste-neutral tales of equality and open-mindedness. They reflect a society deeply embedded in hierarchy, where even gods and gurus reinforced the system—not dismantled it.

Enter the Constitution: A Counter-Revolution

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the architect of the Indian Constitution, saw the Manusmriti as the root of caste-based oppression. In a landmark event in 1927, he publicly burned a copy of the Manusmriti at Mahad.

Ambedkar was clear: the struggle for Dalit rights required discarding texts that sanctified inequality.

The Constitution of India, adopted in 1950, did just that:

- Article 14: Equality before law

- Article 15: Prohibition of discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth

- Article 17: Abolition of untouchability

| Issue | Manusmriti | Indian Constitution |

|---|---|---|

| Caste | Birth-based hierarchy: Brahmins > Shudras | Caste discrimination is illegal |

| Women’s Rights | Women are under male guardianship all life | Equal rights, voting rights, and autonomy for women |

| Social Mobility | No upward movement in caste system | Meritocracy and reservation to uplift oppressed |

| Justice | Unequal punishments based on caste | Equality before law (Article 14) |

| Source of Authority | Divine (Brahma’s will, dharma) | No upward movement in the caste system |

The Battle Today: Democracy vs Dharma?

Despite being a legal non-entity, Manusmriti still haunts the Indian psyche. It resurfaces during debates on women’s rights, caste quotas, temple entry, and interfaith marriages.

Right-wing groups often glorify ancient Hindu texts without clarifying whether they endorse every verse. In doing so, they risk reinforcing Manusmriti-style morality over constitutional values.

Even subtle attempts to reframe India as a ‘Hindu Rashtra’ echo Manusmriti’s vision of a Brahmin-guided state. But the Indian Constitution stands as a firewall against such regression.

Let’s bust another WhatsApp-certified myth: “The caste system is gone, yaar. We’re all equal now.” Really?

Then someone should tell the 90% of Indians who still marry within their caste, according to the India Human Development Survey. Love might be blind, but in India, it sure carries a caste certificate.

And before you say it’s just a village problem—hold your horses (unless you’re Dalit and riding one, which has literally gotten people attacked). Even in cities, try renting a flat with a ‘lower-caste’ surname and watch society’s invisible gates slam shut.

Meanwhile, manual scavenging—yes, the same inhuman job our laws supposedly banned—is still being done by tens of thousands, almost all Dalits, as per the 2023 NCSK report. “But we don’t see caste!” say many, probably while casually making caste-based jokes or choosing school friends, business partners, and temple priests from “their kind.” The crimes haven’t stopped either—over 50,000 atrocities against Scheduled Castes were recorded just in 2022.

But the real trick of modern casteism? It’s not gone—it just put on a tie and got a LinkedIn profile. Today, caste hides behind buzzwords like “merit,” “culture,” and “tradition,” while continuing to control access to power, privilege, and even your dinner guest list. So no, caste isn’t dead. It just got really good at pretending it’s not invited to the table, while quietly deciding the menu.

So, What’s at Stake?

This is not about ancient vs modern. It’s about which values guide our present:

- Birth or merit?

- Divine hierarchy or democratic equality?

- Immutable rules or evolving justice?

Hinduism itself is not synonymous with Manusmriti. The Rigveda, for instance, speaks of unity and mutual respect:

- “Let us move together, let us sing together, let us come to know our minds together.” (Rigveda 10.191.2)

Conclusion: A Choice We Must Make

Ah yes, the classic “Manusmriti is irrelevant today” argument—sounds nice on paper, just like equality at an upper-caste wedding. Let’s be honest: while no one’s reading Manusmriti before bedtime, its values are sneakily embedded in our social DNA.

From the caste-based marriage preferences on matrimonial sites to the informal glass ceilings in elite educational institutions, Manusmriti’s spirit seems to have skipped cremation. Even Dr. Ambedkar didn’t just burn the book for drama—he was symbolically torching a system that still breathes through unwritten codes.

Sure, the Constitution replaced it on paper, but you don’t need a book to enforce an idea—just generations of cultural programming. So no, Manusmriti isn’t gone. It just went incognito.

The Manusmriti represents a frozen moral order. The Constitution represents a living social contract. One looks backward to a mythic past; the other forward to an inclusive future.

In choosing which one to follow—in our laws, our politics, and our everyday biases—we are choosing what kind of India we want to live in.

We already made that choice in 1950. Let’s not rewrite it in invisible ink.