In 2017 when Emma Martina Luigia Morano from Italy died, she was the last person from the 19th century to be alive. Little did we, who are born in the 20th or 21st century know that people in that century experienced freezing temperatures in July, a killer frost in August. This was the darkest and most unusual weather ever seen for people then. This was the summers of 1816 also known as the ‘Year Without a Summer’

Nearly two centuries ago, 1816 was the year without a summer for millions of people in the world. Most hard – hit were the parts of North America and Europe, leading to failed crops and near-famine conditions. Countries like India and China were not doing well either. The huge fall in temperature lead to the abrupt monsoon season and extreme weather.

Historians today have mostly recognized the cause of the infamous “year without a summer” of 1816, at least indirectly, with the invention of the bicycle and the writing of the classic novel “Frankenstein.”

Little did they know that invention of the bicycle was also caused due to the events of the infamous year without a summer. Agricultural failure was widespread during this time, which led to a massive increase in food prices.

This also increased the price of oats for horses, who were the main transportation source at the time, according to the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

People had to look for an alternative to horses as it became very difficult to feed them when getting food to eat was a luxury. This has been credited with helping inspire the invention of the bicycle by Karl Drais in 1817.

What caused the ‘Year Without a Summer’?

We did not have the resources to know what caused the event during those times. But advancement in technology, enabled scientists and historians to uncover the cause.

It was the biggest volcanic eruption in human history, on the other side of the world — Mount Tambora in Indonesia in April 1815 — which threw millions of tons of dust, ash and sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere, temporarily changing the world’s climate and dropping global temperatures by as much as 3 degrees.

The Earth was already in a centuries-long period of global cooling that started in the 14th century. Today, we know it as the Little Ice Age, it had already caused considerable agricultural distress in Europe.

The Little Ice Age’s existing cooling was made worse by the eruption of Tambora, which occurred near the end of the Little Ice Age.

The year brought a lot of distress to people

Apart from the huge food shortages, natural climate change also caused disease outbreaks, widespread migration of people looking for a better (read warmer) home, and religious revivals as people tried to make sense of sudden change in life due to the calamity.

And it could happen again. Big volcanoes can erupt at any time and with little warning, potentially changing the climate and giving a temporary respite to man-made global warming.

To understand the scale of the disaster, consider this, the eruption of Tambora, on April 10, 1815, on the island of Sumbawa in what’s now Indonesia, was 100 times more powerful than the 1980 Mount St. Helens blast, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, which ranked the eruption as a seven on its eight-level volcanic explosivity index.

The volcano blew out enough ash and pumice to cover a square area 100 miles on each side to a depth of almost 12 feet, according to the book, The Year without Summer, by Klingaman and his father, William K. Klingaman.

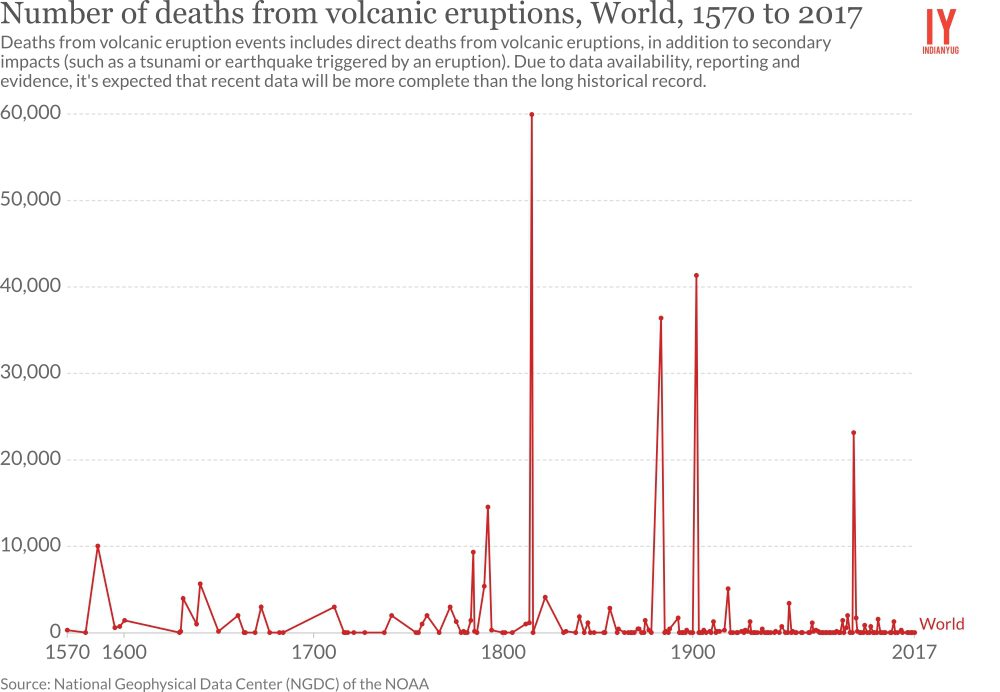

It was by far the deadliest volcanic eruption in human history, the Klingamans wrote, with a death toll of at least 71,000 people, up to 12,000 of whom killed directly by the eruption. See the sharp spike in the year 1915 in the chart above.

When a volcano erupts, it does more than blow out clouds of ash, which can cool a region for a few days and disrupt airline travel. It also spews sulfur dioxide, NASA reports.

A strong enough eruption shoots that sulfur dioxide high into the stratosphere, more than 10 miles above Earth’s surface. At that height, sulfur dioxide reacts with water vapor to form sulfate aerosols.

Because these aerosols float above the altitude of rain, they don’t get washed out by rain and water. Rather, they linger, reflecting sunlight and cooling the Earth’s surface, which is what caused the weather and climate impacts of Tambora’s eruption to occur more than a year later.

The summers were no more like your usual summer season

Heavy snow fell in northern New England on June 7-8, with 18- to 20-inch high drifts. In Philadelphia, the ice was so bad “every green herb was killed and vegetables of every description very much injured,” according to the book American Weather Stories.

Frozen birds dropped dead in the streets of Montreal, and lambs died from exposure in Vermont, the New England Historical Society said.

On July 4, one observer wrote that “several men were pitching quoits (a game) in the middle of the day with heavy overcoats on.” A frost in Maine that month killed beans, cucumbers, and squash, according to meteorologist Keith Heidorn. Ice-covered lakes and rivers as far south as Pennsylvania, according to the Weather Underground.

By the time August came, more severe frosts further damaged or killed crops in New England. People reportedly ate raccoons and pigeons for food, the New England Historical Society said.

Things in Europe were not good either, the cold and wet summer led to famine, food riots, the transformation of stable communities into wandering beggars, and one of the worst typhus epidemics in history, according to The Year without Summer.

In China, the cold weather killed trees, rice crops, and even water buffalo, especially in the north. Floods destroyed many remaining crops.

The monsoon season was disrupted, resulting in overwhelming floods in the Yangtze Valley. In India, the delayed summer monsoon caused late torrential rains that aggravated the spread of cholera from a region near the Ganges in Bengal to as far as Moscow.

In Japan, which was still exercising caution after the cold-weather-related Great Tenmei famine of 1782–1788, the cold damaged crops, but no crop failures were reported, and there were no adverse effects on the population.

Scientists’ best estimate is that the global-average temperature cooled by almost 2 degrees in 1816 said Nicholas Klingaman, who is also a meteorologist at the University of Reading in the United Kingdom. Land temperatures cooled by about 3 degrees, he added.

How soon could this happen again?

Historically eruptions matching the scale of Tambora occur once every 1,000 years on average, but smaller events can still heavily impact the climate. Krakatoa’s 1883 eruption in Indonesia resulted in global cooling almost five years later, even though it ejected less material into the atmosphere than Tambora.

Similarly, Pinatubo in 1991 in the Philippines caused global temperatures to cool by about 1 degree. Eruptions of that greatness — about one-sixth the size of the Tambora eruption — happen about once every 100 years.

Any of those other volcanoes could erupt again, perhaps on a scale of Tambora or greater.

The study of how volcanoes impact the climate is relatively new — Scientists didn’t even know about this link between volcanic eruptions and global cooling until the 1960s and 1970s.

With global temperatures at record highs, a massive eruption today could reduce man-made climate change. But the effect would be only temporary — Warming would pick up where it left off once all the stratospheric dust settled out, a process that could a few years or up to a decade.

The result on the people affected by the event, though, could last far longer. The colorful, dusty skies from Tambora’s epic blast inspired some of the British artist J. M. W. Turner’s most spectacular sunset paintings — some of which were painted decades after the eruption.