On June 16, Twitter became the first US-based social media platform to lose legal protection in India, following a series of episodes that increased the disagreement between the government and the social media platform.

Earlier on June 3, Google had to apologize to the Indian state of Karnataka for search results that prominently listed the state’s primary tongue, Kannada, as the “ugliest language in India.”

As the search engine moved to fix the issue, the state’s minister for forest, Kannada, and culture, Arvind Limbavali, threatened legal action.

Later that very week, the minister demanded that Amazon’s Canada outpost apologize after it listed a bikini for sale that featured Karnataka’s flag. When Amazon did not respond, he vowed to take legal action against the e-commerce platform as well.

These events transpired at a terrible time for big IT giants. Throughout this year, the Indian government has gradually increased its pressure to make them comply with law of the land and new amendments that it brings to the way information is shared in India.

On Feb 1, in response to a huge farmer’s protests as well as a Republic Day anti ‘farmer’s bill’ rally that had turned violent, the Indian government ordered microblogging site Twitter to block 1,178 accounts for allegedly spreading misinformation on farmers’ protest.

Twitter initially resisted, only obscuring some accounts and tweets to be viewed only in India but not removing them—until its India-based employees were threatened with prison time.

Manish Maheshwari, Managing Director of Twitter in India, was questioned by a team of the Delhi Police Special Cell in Bengaluru on May 31.

Following multiple such incidents when Delhi Police visited Twitter India offices in Delhi and Gurgaon it complied and permanently banned more than 500 accounts and obscured others from Indians’ view.

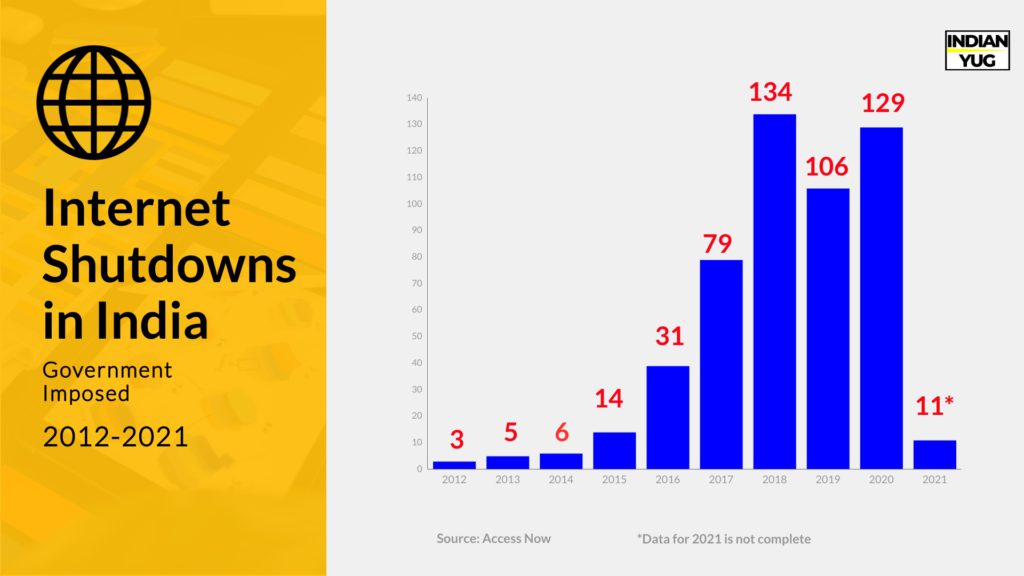

Internet shutdowns in India have been Gradually increasing

Shortly after, the government took matters into its own hands and shut down internet access in areas where protesting farmers were gathering peacefully.

A close look at internet bans in India reveals that it is largely used by the government to curb protests under the garb of national security.

In 2019/20, India had the most cases of internet shutdowns, even after excluding those in Jammu & Kashmir (J&K).

You can trace this in part through regional and local internet shutdown rates: India’s Software Freedom Law Center, which keeps track of these shutdowns, shows that the country saw only three internet shutdowns in 2012, five in 2013, and six in 2014.

Then they surged: 14 in 2015, 31 in 2016, 79 in 2017, 134 in 2018. The number dropped to 106 in 2019 but rose again to 129 in 2020.

Twitter’s transparency unit also has an eye-popping chart showing that the number of Indian government requests for information from Twitter increased exponentially over the past decade, from just 19 total requests in 2012–13 to 2,613 requests in just the first half of 2020.

New guidelines for social and digital media companies

Later that month, India’s Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology implemented new guidelines for social and digital media companies, forcing them to:

1) Disclose the identities of senders of tweets and even anonymous, encrypted messages upon government request

2) Disclose details about how and where certain posts and videos are published

3) Hire Indian residents to special positions to ensure the companies stay in contact with law enforcement agencies, redress grievances, and comply with new rules.

The government maintained that the new regulations would “help protect national security, maintain public order and reduce crime,” though “tech companies say the rules are inconsistent with democratic principles.”

The ministry gave “major” social platforms—defined as networks with more than 5 million regular users—a three-month timeline, ending May 25, to follow these orders or risk being completely banned from India.

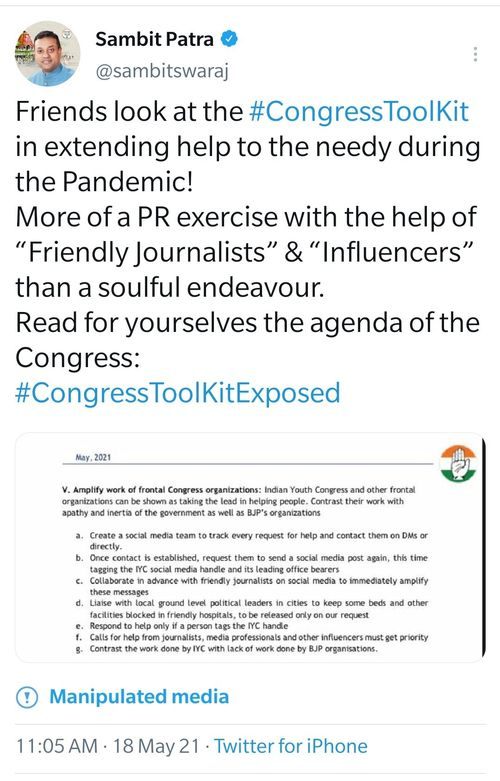

A recent spat with Twitter as BJP spokesperson tweet flagged as manipulated media

The police acknowledged they went to Twitter India’s offices to hand the third notice after finding the replies of the Managing Director “ambiguous”.

Twitter had been asked to clarify why BJP spokesperson Sambit Patra’s tweet on May 18, which had screenshots of what he called a “Congress toolkit” aimed at discrediting Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the government’s handling of Covid, were flagged “manipulated media”.

The flag appeared after Congress wrote to Twitter saying the alleged “toolkit” was fake and that it had filed FIRs against BJP leaders who had tweeted the documents. Some fact-checking websites also described the toolkit as forged.

Modi governement complained to Twitter that the label was applied “prejudicially,” asked the site to remove the labels (which it still has not done), and also requested that it take down posts referring to the so-called Indian variant of the coronavirus.

Details of the questioning from the Twitter India head are emerging at this time, but Twitter faces charges including inciting communal hate over posts on an assault on a Muslim man in Uttar Pradesh’s Ghaziabad on June 5.

In another case filed on Tuesday night, Twitter has been accused of not removing “misleading” content linked to the incident. The serious charges it faces include “intent to a riot, promoting enmity and criminal conspiracy”.

The man, Sufi Abdul Samad, had alleged that his beard was cut off and he was forced to chant “Vande Matram” and “Jai Shri Ram” by a group that assaulted him.

The UP police said was nothing communal about the incident — the man was attacked by six people — Hindus and Muslims – who were angry with him for allegedly selling fake good luck charms.

In this particular case, the police FIR charges Twitter, several journalists, and opposition Congress leaders for inciting “communal sentiments” with posts sharing the man’s allegations.

The cases against Twitter and individuals who Tweeted the video of a man being assaulted and then coming on camera to allege a communal angle are based only on the statement of the UP police.

Government sources say Twitter can no longer claim legal protection in India from prosecution over users’ posts as it has failed to comply with new IT rules requiring it to appoint India-based officers, including a Chief Compliance Officer.

Union IT Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad said Twitter was given “multiple opportunities to comply” but it chose the path of “deliberate defiance”.

A lull before the storm

In the meantime, social media companies appeared to mostly comply with the Indian government’s dictates. In late April, the country’s government asked Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter to take down more than 100 posts—52 of them on Twitter—from politicians, actors, and other prominent figures that bashed the administration’s shoddy pandemic response.

Twitter in turn restricted the tweets so Indian users only could not view them. It was, however, readily available to be read in other countries.

In another incident, Facebook hid posts containing the hashtag #ResignModi—referring to India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi—within India before restoring them in the course of a few hours.

Later a Facebook spokesman said, “we temporarily blocked this hashtag by mistake, not because the Indian government asked us to.” Many were not convinced and wondering if the government has some role in it.

Also, it was widely being reported that Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube each took down posts that inveighed against the Modi administration.

During the ravaging second wave of the Covid19 pandemic — as Indians turned to social media to beg one another for help in the midst of a COVID catastrophe, groups providing resources on messaging apps like Telegram, WhatsApp, and Discord were threatened by police and subsequently disbanded.

When the platform didn’t act on either, police raided Twitter India’s offices in New Delhi and Gurugram (the latter of whose outposts were permanently closed) in order to formally serve notice of the government’s inquiry into the “manipulated media” posts.

The day after the raids was May 25—the deadline for tech companies’ compliance with the new Indian rules. By that time, no platforms besides the India-based Twitter competitor Koo had followed the orders.

The same day, Google and Facebook (which owns WhatsApp) declared their intent to work toward compliance, even as they claimed to be discussing further concerns about the rules with India’s government.

On May 27, Twitter’s Global Public Policy team stated the website would “strive to comply with applicable law in India”—but also called out “recent events regarding our employees in India and the potential threat to freedom of expression for the people we serve,” decried the police raids as “intimidation tactics,” and proclaimed the platform would “advocate for changes to elements of these regulations that inhibit free, open public conversation.”

By June 1, India had given Twitter another three weeks to fully comply with its guidelines. And it appeared, by this week, that Twitter was steadily giving in to government demands.

TechCrunch reported Monday that per the government’s request, the social network had obscured from Indian view four accounts that had criticized Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

But the government also sent Twitter a letter offering a “final warning” this week, according to British tech outlet the Register, demanding it follows the rules after it was revealed that some of the officials appointed by Twitter in the interest of rules compliance were in fact not based in the company’s Indian offices.

Media censorship was commonplace in India decades before the internet reached its borders, and social media censorship predates Narendra Modi’s rule. Yet both have ramped up significantly since the demagogue was elected prime minister in 2014.

Big Tech clash with Modi Government ahead

It once made obvious business sense for Big Tech to focus on India. When digital companies expanded to international audiences throughout the globalizing 2000s, they found a perfect receptor in the Asian subcontinent: an increasingly online, billion-strong, newly capitalist nation ready to welcome foreign business, export its own knowledgeable tech workers to other nations, and join virtual forums to connect with the world and complement South Asia’s historic traditions of argument, democracy, and neighborly goodwill.

Modi, who was praised upon his first election as “India’s first social media prime minister” for his campaign team’s digital savvy, leveraged this social media know-how to become a darling of Silicon Valley in ways previous Indian leaders never did.

His “Digital India” campaign (whose website, incidentally, has pretty horrid design) was praised by various major tech CEOs for its goal of turning India into a utopia of tech innovation; the prime minister visited California-based corporations and held both public and private events with executives from Facebook, Twitter, Apple, and Tesla; investors went gaga over India’s domestic startups.

The founding director for Twitter India joined the company in 2012 with hopes that the platform would help strengthen democracy in the country. It once may have seemed that India, which already had its own “Silicon Valley” for tech innovation within the city of Bangalore, would become both one of the primary drivers and biggest beneficiaries of an interconnected world.

But this quickly crumbled, and the bargain tech execs drove in embracing an already-notorious figure as Modi became much harder.

In 2016, India blocked Facebook’s “Free Basics” initiative, an attempt by the company to offer free internet access through a network of Facebook-approved sites, out of concern that the program would have created unfair tiers for internet access; that same year, Amazon found itself disfavored by the Indian government as it attempted to puncture the subcontinent’s e-commerce market and compete with native Indian companies in the sector.

It’s perhaps only a matter of time before differences between Modi and Big Tech become too stark to ignore.

Far more worrying were the accounts of social impact. Again in 2016, whistleblowers from 2014 BJP campaigns came out publicly about the kind of work they reportedly did for the party’s “IT cells”—namely, coordinated efforts to target and troll BJP opponents across various social platforms, spread misinformation, and counter and shut down criticisms of Modi and his ideological brethren.

More and more stories were reported of calls for mob violence and rampant misinformation spreading throughout WhatsApp, which continued throughout the pivotal 2019 election that Modi and the BJP won in a sweep.

That year, as China’s TikTok became megapopular within India, a local court banned the app for propagating “illicit” content. Soon after, the ban was reversed, only to be reinstated by the national government in summer 2020 in retaliation against China following heated border clashes.

In 2020, the Wall Street Journal reported that India’s then–Facebook head opposed applying the company’s hate speech rules to BJP politicians who’d spouted Islamophobic rhetoric online.

No major Big Tech company has yet hinted to leave or boycott India in response to this increasing conflict—in fact, some are still investing billions in the nation.

However, it’s perhaps only a matter of time before differences become too stark to ignore. Facebook employees, according to the Times, are frustrated with the company over its handling of India’s political situation.

Twitter’s India employees remain worried for their safety—and Modi Government is pushing its own Twitter-like app, Koo, in order to draw its populace away from the American platform and its rules. As tech writer Pranav Dixit has reported, Koo, which is embraced and used frequently by BJP politicians, is saturated with hate speech.

This is in line with India’s attempts to create its own domestic TikTok competitors and get Indians on board with homegrown apps that notably answer only to the Indian government, and no other country or authority.

The India that Silicon Valley once so loved has long given way to a different one: an increasingly authoritarian regime that wants even tighter control over information dissemination.

It’s an India that’s not only willing to bully the very companies it once welcomed in order to firm up its grip, but also one that’s attempting to craft its own parallel social mediasphere as a bargaining chip to Silicon Valley: Either you play by our rules, or we don’t need you.

Internet bans from monitoring content to curbing voices is a dangerous trend in a democracy. What the government needs to do is ensure that internet access is not restricted even if there is opposition from a section of the people.

It is important to provide a platform for voices of dissent in a democracy. Second, like in the US, the Indian government should also start a process to ensure that puts a check on the excessive power of any organization over data and information using the internet.

More importantly, what the government needs to realize is that at a time when it promoting Digital India, Smart Cities and Aadhar-based know your customer (KYC) for banks, such bans turn counter-productive.

Also, such curbs do not reduce violations or the spread of misinformation. What is needed is effective governance at the ground level rather than bans on internet connectivity.

The country faces the greatest loss globally due to internet shutdowns. It’s time to go in for focused and limited period shutdowns if at all and as the world’s largest democracy show that such bans don’t really work.